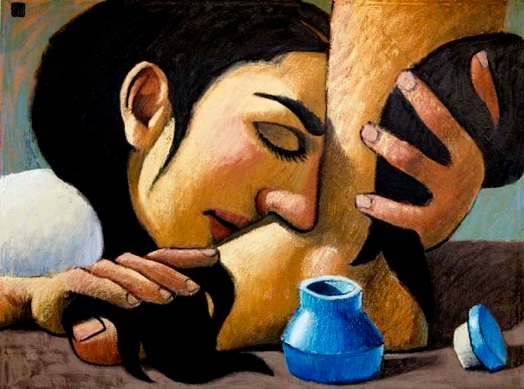

Extravagance. Pleasure. Effusiveness. Exuberance. These aren’t ideas that we usually associate with Lent and the overture to Jesus’ passion. But Mary of Bethany understands differently. — Matt Skinner

Have you ever seen or experienced someone physically caring for a loved one in preparation for that dying person’s death? — Edward F. Markquart

***

Text: John 12:1-11 — Mary Anoints Jesus

12 Six days before the Passover Jesus came to Bethany, the home of Lazarus, whom he had raised from the dead. 2 There they gave a dinner for him. Martha served, and Lazarus was one of those at the table with him. 3 Mary took a pound of costly perfume made of pure nard, anointed Jesus’ feet, and wiped them[a] with her hair. The house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume. 4 But Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples (the one who was about to betray him), said, 5 “Why was this perfume not sold for three hundred denarii[b] and the money given to the poor?” 6 (He said this not because he cared about the poor, but because he was a thief; he kept the common purse and used to steal what was put into it.) 7 Jesus said, “Leave her alone. She bought it[c] so that she might keep it for the day of my burial. 8 You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me.”

Meditations for Monday and the events of Holy Week:

“Is it not true that only when we have been helped by God, that we begin to understand how to live extravagantly in honouring Christ wherever we may find him?” — Peter Woods

So what is it about Mary’s extravagance that merits Jesus’s blessing, and what is it about Judas’s criticism that earns Jesus’s rebuke? Mary responds to the call of love in the moment. In the now. Knowing what Jesus is about to face; knowing that he’s in urgent need of companionship, comfort, and solace; knowing that the time is short to express all the gratitude and affection she carries in her heart, Mary acts. Given the choice between an abstracted need (the poor “out there”) and the concrete need that presents itself at her own doorstep, around her own dinner table, Mary chooses the here and now. She loves the body and soul who is placed in her presence. In doing so, she ends up caring for the one who is denied room at the inn — even to be born. For the one who has no place to lay his head during his years of ministry. For the one whose crucified body is laid in a borrowed tomb. In other words, it is the poor Mary serves when she serves Jesus. Just as it is always Jesus we serve when we love without reservation what God places in front of us, here and now. Lutheran minister Reagan Humber puts it this way: “What won’t always be with us is the opportunity to see God in whatever and whomever stands in front of us right now. The kingdom of God is here. Right now is the moment when God can break our hearts. The love of God is the grace of now.” — Debie Thomas

“If we want to dialogue with the Scriptures, we must expose ourselves to the political, social, economic, cultural, and religious situations of the ancient world where the writings were born and where the people did not necessarily enjoy peace and justice.” — Hisako Kinukawa

“Remember finally, that the ashes that were on your forehead are created from the burnt palms of last Palm Sunday. New beginnings invariably come from old false things that are allowed to die.” — Richard Rohr

“No pain, no palm; no thorns, no throne; no gall, no glory; no cross, no crown.” — William Penn

Compassionate Pedicure Scene from On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: A Novel — Ocean Vuong

A prosthesis. Halfway down her shinbone, a brownish stub protrudes, smooth and round as the end of a baguette—or what it is, an amputated leg. I glance at you, hoping for an answer. Without skipping a beat, you take out your file and start to scrub her one foot, the puckered nub beside it shaking from the work. The woman places the prosthesis at her side, her arm resting protectively around its calf, then sits back, exhaling. “Thank you,” she says again, louder, to the crown of your head.

I sit on the carpet and wait for you to call for the hot towel from the warming case. Throughout the pedicure, the woman sways her head from side to side, eyes half-closed. She moans with relief when you massage her one calf. When you finish, turning to me for the towel, she leans over, gestures toward her right leg, the nub hovering above the water, dry this whole time. She says, “Would you mind,” and coughs into her arm. “This one also. If it’s not too much.” She pauses, stares out the window, then down at her lap. Again, you say nothing—but turn, almost imperceptibly, to her right leg, run a measured caress along the nub’s length, before cradling a handful of warm water over the tip, the thin streams crisscrossing the leathered skin. Water droplets. When you’re almost done rinsing the soap off, she asks you, gently, almost pleading, to go lower. “If it’s the same price anyway,” she says. “I can still feel it down there. It’s silly, but I can. I can.”

You pause—a flicker across your face. Then, the crow’s-feet on your eyes only slightly starker, you wrap your fingers around the air where her calf should be, knead it as if it were fully there. You continue down her invisible foot, rub its bony upper side before cupping the heel with your other hand, pinching along the Achilles’ tendon, then stretching the stiff cords along the ankle’s underside. When you turn to me once more, I run to fetch a towel from the case. Without a word, you slide the towel under the phantom limb, pad down the air, the muscle memory in your arms firing the familiar efficient motions, revealing what’s not there, the way a conductor’s movements make the music somehow more real. Her foot dry, the woman straps on her prosthesis, rolls down her pant leg, and climbs off. I grab her coat and help her into it. You start walking over to the register when she stops you, places a folded hundred-dollar bill in your palm.

— Ocean Vuong